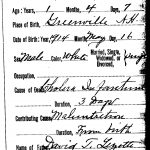

This image may be a strange way to start a blog on justice, but bear with me. This is the death certificate of Joseph Arthur Calixte Lizotte in Greenfield, New Hampshire. For the record he’s my 7th cousin twice removed, though I doubt I would have ever met or heard of him had he lived. The death certificate is hard to read, but he died in 1915 at 16 months of cholera (that he had for 3 days) and malnutrition (that he had for his entire life).

I came across this death certificate about 10 years ago when I was doing genealogy research and was struck and saddened by the fact that someone could die (at least partly) from malnutrition here in the United States. Simply put, the programs that would have saved him wouldn’t exist until 20 years later when the country was in the middle of a depression.

As I look over the political landscape today I worry that we may be headed back to those days. The Great Depression lasted only a decade but framed much of the 20th Century. Talk to nearly anyone who lived through those years and he will tell you that it was when people came together to help each other. It was also a time when our nation began to reflect on common values. Led by President Franklin Roosevelt (1882-1945) we developed programs to support the elderly (Social Security), the poor (Welfare, later known as Aid to Families with Dependent Children), and the unemployed (Works Progress Administration, Civilian Conservation Corps, and others). In later years help was expanded to include the hungry (Food Stamps). By the 1960s we began to provide health care to the elderly and the poor (Medicare and Medicaid).

Though far from complete, these programs ensured that most of the basic needs of most of us are provided. If my distant cousin had been born in 1934 instead of 1914 he likely would not have spent his entire life suffering from malnutrition. Because of progress made in plumbing and cleanliness he probably wouldn’t have even developed cholera, but if he did he would have had an 80% chance of surviving it (see the CDC for more information). All these programs were funded through the taxes we paid, and we paid them because they reflected our values.

Fast forward to today. I’m not sure we still share those values; as I read the political landscape, the only real value I see is that I should not be inconvenienced or charged for anything that will benefit anyone other than me. If you’re running for office, the fastest road to defeat lies in not promising to cut taxes. It’s become fashionable to claim that government does too much and is too costly. Meanwhile, on ground level, our schools, fire departments, libraries and infrastructure are crumbling. We are laying off teachers while school attendance continues to rise.

We’re also making it harder to access services. In 2008 here in San Diego, only 29% of those eligible for food stamps actually received them. Why not? These answers are always complicated but I don’t think anyone can deny that the process of applying is difficult and humiliating. Fortunately there has been some publicity around this and more hungry people are accessing food stamps, but the number is still too low.

This will ensure I can never run for office on any level, but I think we need to be willing to pay for what we value and be frank that we are all invested in good schools and full stomachs. We, as a whole, need to be compassionate not just with our minds but also with our wallets. We need to live in a society where nobody dies (even in part) of malnutrition.